Flowers Reimagined Through Light

“The first impression, especially at this height on leaning over this gulf of light, is a sort of vertigo; at first, across the waves of light from the mirrors, the glitter of the gold, the sparkle of the diamonds, the flash of the jewels, and the sheen of rich material, nothing can be distinguished. A swarmlike scintillation prevents you from seizing any forms; then soon the pupil grows accustomed to the dazzle and chases the black butterflies that flutter before it as after looking at the sun.”

— Théophile Gautier, “The Court Ball,” in Romantic Castles and Palaces [1].

Nineteenth-century audiences did not necessarily experience diamonds as static decorations but rather as active sources of light. Court balls and evening entertainments were remembered for their glare and shimmer, where diamonds flickered, glowed, and blurred the outlines of bodies. Contemporary descriptions repeatedly emphasised movement, brightness, and optical excess, revealing a way of seeing jewellery that privileged radiance over colour or material mass.

Several of the diamond botanical sprays now in the Victoria and Albert Museum belong firmly to this visual world. Produced between roughly 1830 and 1900, these three-dimensional floral ornaments reimagined flowers through light rather than hue. Constructed entirely from diamonds, they rely on optical effects and sculptural modelling to make botanical form legible. Rather than imitating the colours of living plants, they translate flowers into structures of brilliance, scintillation, and movement.

This essay argues that diamond botanical sprays function as spectral reinterpretations of flowers. Their recognisability depends on Victorian floral culture, exhibition practices, and the distinctive optical properties of diamond, which together enabled flowers to be rendered convincingly without colour.

Victorian Floral Culture and the Language of Flowers in Jewellery

Flowers in general occupied an essential and central place in Victorian social and visual life. They appeared in dress, hair, interiors, and ceremonial settings, and real floral sprays were routinely worn at weddings and evening entertainments [2]. This immersion formed part of a broader enthusiasm for natural history, a cultural passion that trained audiences to look closely at the natural world and sharpened habits of visual attention [3].

Floral imagery also shaped Victorian ideals of femininity. Visual culture repeatedly aligned women and flowers through associations of beauty, delicacy, and moral virtue [4]. Botanical study reinforced this familiarity. Botany became an accessible leisure pursuit for women, who learned plant structure through drawing, collecting, and domestic instruction. These activities fostered botanical knowledge grounded in visual observation rather than professional science [5].

Representational practices further refined this visual literacy. Wax flower modelling, for example, produced highly accurate replicas of plants, often even displaying them in multiple stages of bloom. Described as ‘fac-similes of nature,’ these objects encouraged viewers to focus on petals, buds, and structural rhythms independent of colour [6]. The domestic garden likewise sustained daily engagement with plant form. Gardening manuals aimed at women framed the garden as a site of practical authority and aesthetic judgement, reinforcing expectations that women possessed an instinctive and inherent sensitivity to floral structure [7].

At the same time, the popularisation of botany increasingly emphasised sight as the primary means of understanding plants. Classification systems relied on visible characteristics, encouraging viewers to identify species through form, proportion, and arrangement rather than through smell or touch [8]. Within this visual culture, jewellers could assume a shared and widely understood botanical vocabulary. Even without colour, flowers could be recognised through their structural features alone.

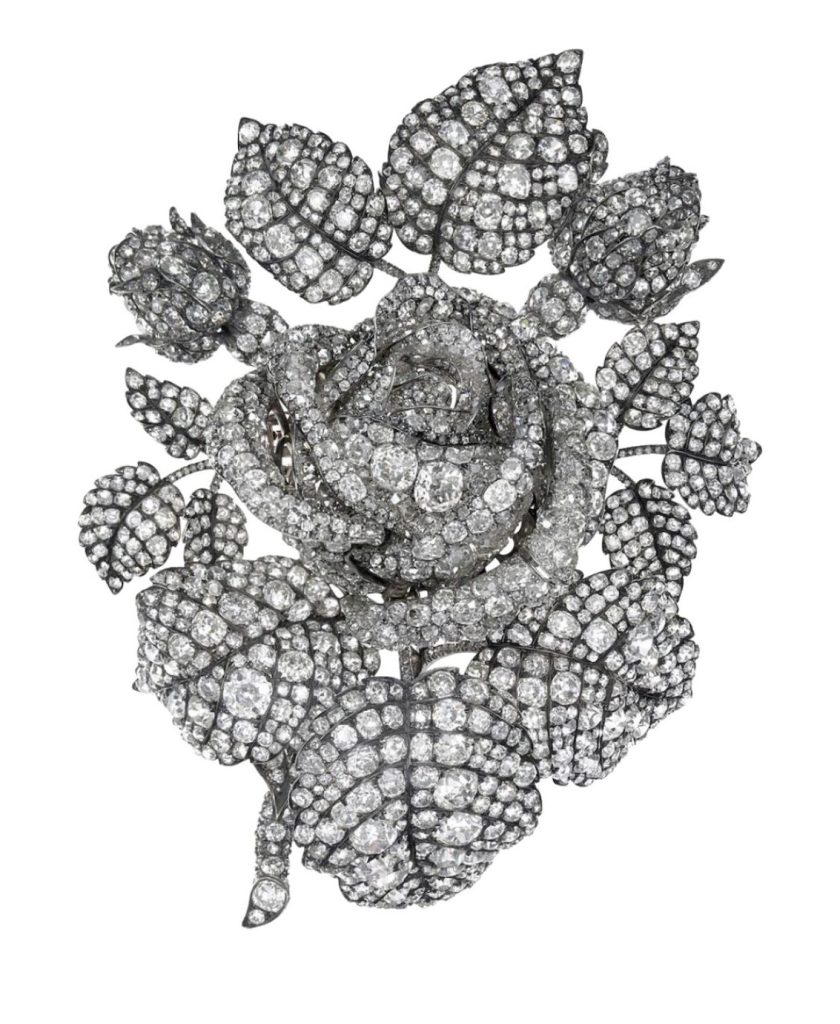

A small diamond convolvulus spray tied with a ribbon (M.140C-1951), for example, depends on the immediate recognisability of trumpet-shaped blossoms. Princess Mathilde’s rose spray by Mellerio of 1864 demonstrates this most clearly. Composed of over 2,300 diamonds, the rose appears full, rounded, and actively blooming. The petals curve outward with convincing depth, creating a dynamic and volumetric form. The jewel is visually active, showing how Parisian jewellers used three-dimensional modelling to articulate botanical identity without colour [9]. Viewers accustomed to reading flowers across gardens, illustrations, wax models, and decorative arts could readily identify both species and sentiment in such diamond blooms.

Naturalism Without Colour: Diamond Flowers in Nineteenth-Century Jewellery

Much of mid-nineteenth-century botanical jewellery relied on colour to achieve naturalism. Enamel, foiled glass, and coloured gemstones allowed jewellers to imitate the hues and textures of living plants. Mellerio’s lilac spray of 1862 exemplifies this approach. Its buds deepen in tone, its blossoms soften into pale purples, green enamel defines the leaves, and moonstones serve as translucent dew drops [10].

Similarly, Tiffany & Co.’s orchid brooch, exhibited at the 1889 Exposition Universelle, employed a wide range of enamelled hues and patterned surfaces. Contemporary critics praised such works for their illusionistic accuracy and chromatic richness [11].

Against these examples, diamond botanical sprays appear deliberately austere. Although diamonds produce flashes of spectral colour through dispersion, their overall effect remains one of whiteness when compared with enamelled or gemstone-set flowers. This is particularly striking in a culture that attached strong emotional and symbolic meaning to floral colour [12]. By eliminating hue, diamond sprays shift emphasis from chromatic description to structural observation. Scale, proportion, petal arrangement, and botanical rhythm become the primary means of communication.

A large diamond bouquet spray in the Victoria and Albert Museum (M.115-1951) demonstrates this approach. The asymmetrical composition appears to curl around the body when worn and combines multiple flower types within a single arrangement. Roses, carnations, anemones, and columbine remain identifiable through subtle variations in petal structure and orientation. Several elements are mounted en tremblant, allowing them to quiver with the wearer’s movement. This controlled vibration animates the jewel, producing rapid flashes of light that compensate for the absence of colour.

This strategy recalls Mellerio’s diamond-set snowdrops, patented in 1854 and demonstrated at the Exposition Universelle of 1855, where en tremblant mounts were explicitly praised for their naturalistic effect [13]. In such works, movement becomes a substitute for colour-based realism, reinforcing organic vitality through motion. The absence of colour is therefore not a limitation but an aesthetic choice. Diamond sprays distil the flower to its architectural essence, transforming botanical identity into sculptural form rendered through light.

Diamond as Light: The Optical Properties of Diamond in Nineteenth-Century Jewellery

The effectiveness of diamond botanical sprays depends on how nineteenth-century audiences were accustomed to seeing diamonds. Contemporary accounts describe diamonds as active, overwhelming sources of light, particularly in candlelit interiors. Gautier’s description of a court ball captures this atmosphere vividly, as do other accounts. At the Brighton Pavilion ball of 1807, the Morning Post described a ‘splendid profusion of diamonds’ creating a fairytale-like scene [14]. Harriette Story Paige recalled a London court ball in 1839 as a ‘blaze of jewelry,’ describing the Marchioness of Londonderry as ‘literally covered’ in diamonds [15]. Later, Marie von Bunsen described entering a throne room illuminated by ‘thousand-fold candlelight,’ where ‘all the diamonds sparkled’ with ‘unbelievable glitter’ [16].

These descriptions reveal diamonds as materials defined by glare, shimmer, and optical overflow rather than static form. Diamond botanical sprays relied on this expectation. Their recognisability depended not only on careful modelling but on viewers already trained to interpret diamonds as dynamic, light-producing surfaces.

Several optical properties make this possible. Diamond’s high refractive index prevents transparency, redirecting light rather than allowing the eye to see through the stone. Unlike sapphires or aquamarines, diamonds do not reveal the setting beneath. This refusal of transparency is crucial in three-dimensional jewellery. If the stones allowed windowing, the underlying mounts or the wearer’s clothing would disrupt the floral silhouette. Instead, diamonds function as concentrated points of light, allowing the entire jewel to read as a volumetric object shaped by brightness.

Brilliance stabilises the overall form. In pavé-set areas, individual facets merge into continuous surfaces of light, enabling petals and leaves to appear as unified shapes. Dispersion adds subtle flashes of colour that introduce liveliness without undermining the monochrome aesthetic. Scintillation, produced by movement, reinforces delicacy and natural motion, particularly in en tremblant constructions.

A comparison between the diamond convolvulus spray (M.140C-1951) and a nearly identical turquoise version (M.82-1951) highlights this difference. Although similar in form, their visual effects diverge. The diamond spray appears animated by light, while the turquoise version, set with small cabochons, absorbs light and produces a flatter, quieter surface. Despite its colour, turquoise fails to achieve the same vitality. Diamond thus transforms botanical form conceptually, constructing floral identity through optical behaviour rather than pigment.

Conclusion

The continued production of large articulated diamond sprays by firms such as Bapst et Falize, Tiffany & Co., and Carrington & Co. demonstrates the enduring appeal of this format. Within the competitive environment of international exhibitions, such works showcased technical control, innovation, and the dramatic possibilities of light in motion.

Diamond botanical sprays are not literal replicas of flowers but reinterpretations that translate botanical matter into luminous structures. Their absence of colour, combined with the brilliance, dispersion, and scintillation of diamond, produces a spectral aesthetic in which flowers appear both recognisable and otherworldly. These jewels embody a distinctive intersection of natural observation, material transformation, and nineteenth-century visual culture: flowers reimagined through light.

Leave a comment

Endnotes

[1] Esther Singleton, Romantic Castles and Palaces, as Seen and Described by Famous Writers (London: Forgotten Books, 2018), 127, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77405.

[2] Beverly Seaton, The Language of Flowers: A History (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995), 9–10.

[3] Barbara T. Gates, “Introduction: Why Victorian Natural History?,” Victorian Literature and Culture 35, no. 2 (2007): 539–40.

[4] Annette Stott, “Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition,” American Art 6, no. 2 (1992): 60–61.

[5] Ann B. Shteir, “Gender and ‘Modern’ Botany in Victorian England,” Osiris 12 (1997): 29–31.

[6] Ann B. Shteir, “‘Fac-Similes of Nature’: Victorian Wax Flower Modelling,” Victorian Literature and Culture 35, no. 2 (2007): 649–50.

[7] Sarah Bilston, “Queens of the Garden: Victorian Women Gardeners and the Rise of the Gardening Advice Text,” Victorian Literature and Culture 36, no. 1 (2008): 1–3.

[8] John C. Ryan, “Cultural Botany: Toward a Model of Transdisciplinary, Embodied, and Poetic Research into Plants,” Nature and Culture 6, no. 2 (2011): 124–25; Donald Culross Peattie, “On the Popularization of Botany,” American Journal of Botany 43, no. 7 (1956): 520–22.

[9] Wartski London, ed., From Function to Fantasy: The Brooch. From 1200 BCE to the Contemporary (London, 2025), 138–39.

[10] Wartski London, From Function to Fantasy, 62–63.

[11] Wartski London, From Function to Fantasy, 92–93.

[12] Seaton, The Language of Flowers, 119.

[13] Wartski London, From Function to Fantasy, 61.

[14] Paul Cooper, “A Selection of Balls from 1807,” Regency Dances, n.d., https://www.regencydances.org/paper066.php.

[15] Edward Gray, ed., Journal of Harriette Story Paige, 1839, in Daniel Webster in England (Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1917), 33.

[16] Marie von Bunsen, “A Young Noblewoman Is Presented at Court (1882–83),” trans. Erwin Fink, German History in Documents and Images, n.d., https://germanhistorydocs.org.