Neither simply a jewel nor only a sculpture, a sixteenth-century ring in the collection of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, featuring Vulcan blurs the boundaries between jewellery and sculpture, material and model. Inspired by Michelangelo Buonarroti’s Dusk, one of the monumental allegorical figures carved for the tomb of Lorenzo de’ Medici in the Medici Chapel in Florence, the ring translates a large-scale tomb sculpture into a miniature, hand-held object. Although its precise origin remains unknown, the ring was likely fabricated in Italy between around 1530 and 1560. Despite this likely Italian context of production, the object reflects concerns that were central to Netherlandish sculptural practice in the sixteenth century, particularly the fluid movement between media, scale, and geography.[1]

Image credit: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

The ring appears not to have been conceived primarily as functional jewellery but rather as a sculptural object in miniature. It compresses monumentality into a portable form and reflects the working practices of artists who moved between North and South, and between goldsmithing and sculpture. As this case study will show, the Vulcan ring participates in what Peter Burke has described as processes of cultural translation, in which objects and motifs were not simply transported across borders but actively reinterpreted within new artistic and social contexts.[2]

Image credit: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

From Monument to Miniature

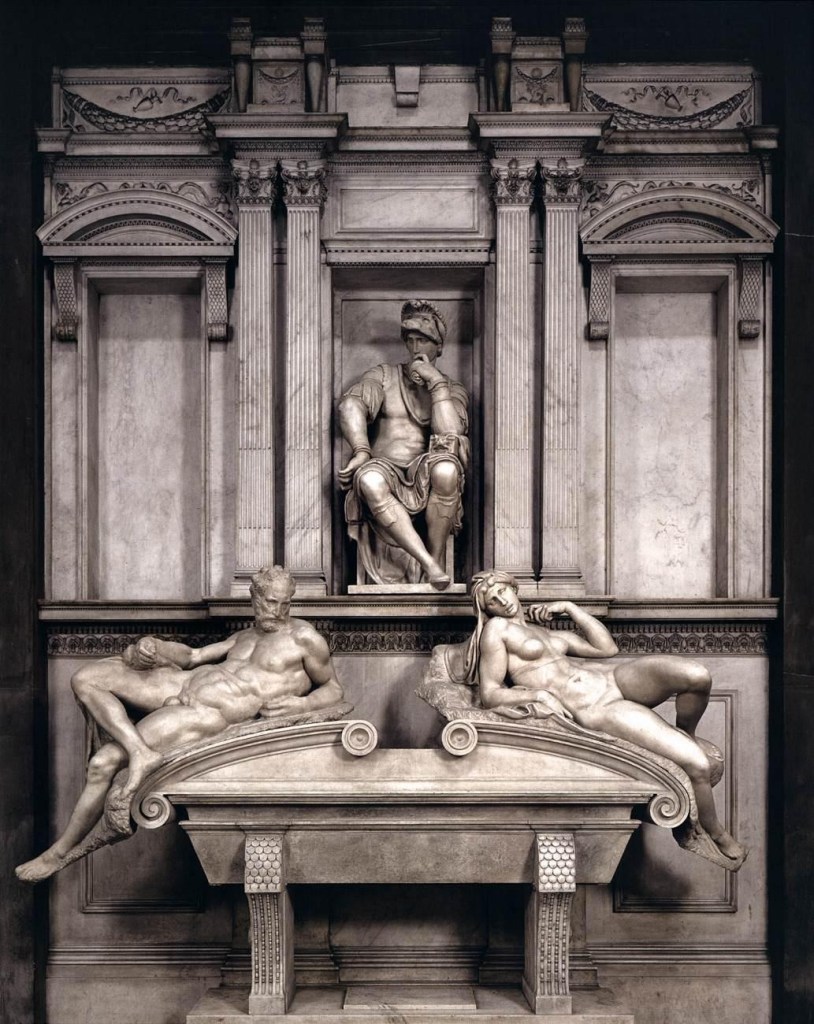

The ring depicts a reclining male nude with one arm twisted behind his back and his legs extended. Both pose and musculature closely reference Michelangelo’s Dusk, carved between 1524 and 1531 as part of the Medici Chapel ensemble. In its original setting, Dusk functioned as part of a monumental architectural programme, paired with Dawn and embedded within a complex allegorical system concerned with time, mortality, and ducal authority.[3]

Image credit: Web Gallery of Art, by Emil Krén and Daniel Marx.

In the ring, this monumental figure is radically transformed. Rendered in gold and silver at a dramatically reduced scale, the nude is stripped of its architectural context. Around the base of the figure, the maker introduced low-relief vegetal forms in silver. These curling elements, absent from Michelangelo’s sculpture, serve a decorative and compositional function, anchoring the figure to the circular logic of the ring and signalling an ornamental rather than architectural framework.

A small anvil placed behind the figure further alters its meaning. Through this addition, the allegorical figure of Dusk is transformed into Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and metalwork. Roman mythology associated Vulcan with technical mastery, invention, and the animation of metal. In Homer’s Iliad, Vulcan forges a fantastical shield for Achilles, populated with miniature cosmic scenes and mechanical wonders.[4] By casting Vulcan in gold and reducing him to a scale small enough to turn in the hand, the maker draws an implicit parallel between the god and the artist. The ring thus becomes a self-reflexive object: a sculpture about making, created through the very skills it celebrates.

An Atypical Jewel

This transformation from tomb sculpture to mythological jewel is highly unusual. While secular figurative jewellery existed in the Renaissance, no close parallels to this ring are currently known. The absence of comparable examples may be partly explained by the historical fate of precious metal objects, which were frequently melted down and reworked to accommodate changing tastes.[5] What survives here is a singular object, detached from a broader material landscape that has largely disappeared.

Stylistically, the ring also stands apart from typical sixteenth-century jewellery. Gold was often valued for its strength and malleability rather than its visual prominence, while gemstones provided colour and brilliance. In contrast, the Vulcan ring contains no stones. The sculpted gold figure itself is the focal point. This choice aligns the object more closely with traditions of miniature sculpture than with conventional jewellery and reinforces the sense that it was intended to be viewed and handled rather than worn.

Mobility and Netherlandish Sculptural Practice

The ring’s hybrid character becomes more legible when placed within the context of sixteenth-century artistic mobility. The period marked a peak in the migration of Netherlandish sculptors across Europe. As Kristoffer Neville has demonstrated, their success often depended on adaptability: the ability to reshape artistic language in response to new environments while retaining technical expertise formed in the Low Countries.[6]

Many Netherlandish sculptors began their careers as goldsmiths. This training fostered a sensitivity to material, scale, and finish that translated readily into bronze casting and sculptural modelling. Wax modelling, chasing, and miniature work formed a core part of this education. Goldsmithing thus provided a technical foundation that shaped sculptural practice long after artists moved into larger media.[7] The Vulcan ring can be understood as a product of this hybrid training, combining Italian sculptural ideals with a Northern emphasis on material intelligence and scale.

Goldsmiths, Sculptors, and Artistic Status

Goldsmiths were expected to be exceptionally versatile. A single practitioner might produce rings, pendants, containers, medals, and sculptural ornaments, often combining multiple techniques within a single object. Benvenuto Cellini, who famously bridged goldsmithing and sculpture, described designing jewellery spontaneously while conversing with clients, emphasising invention as much as execution.[8]

Despite this expertise, a social and artistic hierarchy persisted. In Italy, goldsmiths were often viewed as craftsmen rather than artists, a distinction Cellini repeatedly lamented. He records being told that he “drew too well” for a goldsmith, a remark that reveals the perceived boundary between intellectual design and manual craft.[9] This hierarchy was reinforced by workshop practice, in which design, modelling, casting, and finishing were frequently divided among specialists.

Image credit: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Objects such as the Model for a Jewel with Adam and Eve (c. 1530) complicate this division. Carved as a full-scale pendant design, the model was likely intended to be cast by another specialist, yet it also functions as a sculptural object in its own right.[10] Jewellery models such as this reveal the layered processes through which sculptural jewellery was conceived and demonstrate how goldsmithing and sculpture shared preparatory practices.

Models, Miniatures, and Self-Promotion

The Vulcan ring may have served a demonstrative purpose rather than a wearable one. Its lack of visible wear suggests it was not intended for regular use. Without a maker’s mark or documented ownership, the ring may have functioned as a sculptor’s sample or portable display of skill. Netherlandish sculptors such as Johan Gregor van der Schardt are known to have produced terracotta and wax body-part studies, often based on classical prototypes, which functioned as studio objects and tools of self-promotion.[11]

These small sculptures were not merely preparatory sketches but communicative objects that demonstrated artistic knowledge, technical control, and familiarity with Italian models. The Vulcan ring may have operated in a similar way. Its reference to Michelangelo signals intellectual engagement with Italian art, while its intricate execution showcases the maker’s ability to translate monumental form into precious metal at miniature scale.

Miniature Sculpture and Intimate Viewing

The ring’s small scale aligns it with a broader tradition of micro-sculpture in the Low Countries. Boxwood prayer nuts, intricately carved with dense biblical scenes, exemplify how extreme smallness functioned as a demonstration of skill rather than a limitation. These objects were designed to be turned in the hand and examined closely, rewarding slow, attentive viewing.[12]

Image credit: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Comparable dynamics shaped other hand-held sculptural formats, including medals, which emerged as key sculptural objects in the Renaissance. Medals combined portability with artistic ambition, circulating likeness and skill across courts.[13] Netherlandish sculptors trained in Italy also explored this logic of miniaturisation. Giambologna, for instance, produced a self-portrait bust just 9.2 centimetres high, likely intended for private exchange among friends and patrons.¹⁴ Though fully three-dimensional, the bust functioned much like a medal, reinforcing artistic identity through circulation.

Image credit: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Collecting, Handling, and Wonder

By the later sixteenth century, objects of this kind fit comfortably within elite collecting practices. Cabinets of curiosities combined naturalia and artificialia, bringing together shells, scientific instruments, medals, jewellery, and small sculptures. Painted representations of these collections frequently show jewellery displayed alongside natural wonders, emphasising their capacity to inspire contemplation and study.[15]

Image credit: Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Carved rosary beads, prayer nuts, and cherry stones with miniature faces were particularly prized. While sometimes worn, they were often valued primarily as objects of wonder and ingenuity. Cherry stones carved with dozens of heads, for example, functioned as microcosms of artistic virtuosity and were frequently mounted or displayed rather than used.[16] Like these objects, the Vulcan ring invites handling and close inspection. Turning it in the hand mirrors the viewing practices associated with prayer nuts, medals, and other micro-sculptural works.

Image credit: Green Vault, Dresden State Art Collections.

Conclusion

The Vulcan ring may be small in scale, but it opens a wide field of inquiry into sixteenth-century artistic practice. Likely produced in Italy and inspired by Michelangelo’s Dusk, it nonetheless reflects a sculptural sensibility shaped by Netherlandish traditions of material intelligence, mobility, and miniaturisation. Its transformation of a monumental tomb figure into a mythological jewel is not an act of passive copying but of thoughtful reinterpretation.

Whether conceived as a studio object, a portable demonstration of skill, or a collector’s treasure, the ring exemplifies the subtle processes of cultural translation that shaped early modern sculpture. It invites us to reconsider how jewellery and sculpture intersected, and how small, hand-held objects could participate fully in the broader dialogues of Renaissance art.

Endnotes

- Frits Scholten, “Spiriti Veramente Divini: Sculptors from the Low Countries in Italy, 1500–1600,” in Cultural Exchange between the Low Countries and Italy (1400–1600), ed. Ingrid Alexander-Skipnes (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007), 225–38.

- Peter Burke, “Cultures of Translation in Early Modern Europe,” in Cultural Translation in Early Modern Europe, ed. Peter Burke and R. Po-chia Hsia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 7–38.

- Paul Joannides, “Michelangelo’s Medici Chapel: Some New Suggestions,” The Burlington Magazine 114, no. 833 (1972): 541–51; Estelle Lingo, “The Evolution of Michelangelo’s Magnifici Tomb,” Artibus et Historiae 16, no. 32 (1995): 91–100.

- Homer, The Iliad, trans. Alexander Pope (Project Gutenberg, 2002).

- Joan Evans, A History of Jewellery, 1100–1870 (New York: Dover, 1989).

- Kristoffer Neville, “Virtuosity, Mutability, and the Sculptor’s Career in and out of the Low Countries, 1550–1650,” Artibus et Historiae 39, no. 77 (2018): 291–318.

- Frits Scholten, “A Prayer Nut in a Silver Housing by ‘Adam Dirckz,’” The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 59, no. 4 (2022): 322–47.

- Benvenuto Cellini, The Treatises of Benvenuto Cellini on Goldsmithing and Sculpture, trans. C. R. Ashbee (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger, 2006).

- Benvenuto Cellini, The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, trans. Anne MacDonell (London: Everyman’s Library, 2010).

- Rijksmuseum, Model for a Jewel with Adam and Eve, BK-16987.

- Arjan de Koomen, “‘Una Cosa Non Meno Maravigliosa Che Honorata’: The Expansion of Netherlandish Sculptors in Sixteenth-Century Europe,” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 63 (2013): 82–109.

- Prayer Nuts, Private Devotion, and Early Modern Art Collecting (Riggisberg: Abegg Stiftung, 2017).

- J. Graham Pollard, “The Italian Renaissance Medal,” Studies in the History of Art 21 (1987): 161–69.

- Michael Wayne Cole, Ambitious Form: Giambologna, Ammanati, and Danti in Florence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022).

- Jaś Elsner, ed., The Cultures of Collecting (London: Reaktion Books, 1997).

- Anna Grasskamp, “Shells, Bodies, and the Collector’s Cabinet,” in Conchophilia (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021), 49–71.

Leave a comment