Originally from Wendela Magazine (2025)

1 ring with a faceted stone, 1 gold double hoop presented by my husband, 1 gold bell purchased with 4 small bells, inherited from my mother: 1 string of 50 pearls for the neck…

At first glance, the jewellery descriptions in the section titled ‘Juweelen en keetenen penningh’ (jewels and chains medallions) in Wendela Bicker’s waardeboek seem straightforward. A gold ring sounds like just a gold ring. But when considering what these pieces might have explicitly looked like, things become less certain.

This essay aims to closely explore Wendela Bicker’s jewellery collection by examining at her waardeboek alongside a portrait of her made by Adriaen Hanneman in 1957. Through transcribing, translating, and comparing her inventory with other seventeenth-century records, it aims to build a fuller picture of her jewellery. By combining archival research with visual analysis, this study contributes to a better understanding of jewellery in the Dutch Republic and offers a starting point for further research. Additionally, through drawn reconstructions of her jewellery, it explores how Hanneman’s painted details align with Wendela’s written descriptions, providing a tangible visualization of the possible designs and decorative techniques of her pieces.

Unknown terminology

Interpreting Wendela’s inventory requires an understanding of the specific terminology she used. This essay will now focus on words and phrases in her waardeboek that do not have direct parallels in existing literature on Dutch jewellery history. By analysing these terms in context, this section aims to clarify their meanings and shed light on the ways jewellery was described in the seventeenth century. As there is so little written about jewellery history in the Dutch Republic specifically, wording and terminology used by Wendela has caused some confusion during this process. The three words that appeared unknown in other literature were ‘essenties’, ‘vatsoen’ and ‘versetsteenen’.

The word ‘essenties’ highlights the interactive nature of jewellery creation in the seventeenth century. Unlike the modern practice of purchasing pre-made jewellery, Wendela specifies the cost of the components, the ‘essenties’, necessary to fashion the earrings.[1] The ‘essenties’ Wendela mentions, could be interpreted in two ways. It could be interpreted as ‘esjes’, a word for small gold jump rings used to create jewellery pieces.[2] Or, it could be understood more broadly, as ‘essenties’ translates in modern Dutch to ‘essentials’. In the context of her written jewellery inventory, it seems that Wendela mentions ‘essenties’ to refer to all the materials needed to create her earrings. ‘Esjes’ could have been used, but other materials and components too. Nevertheless, this term highlights the fact that jewellery in the seventeenth century was not necessarily a static possession but often reworked, repurposed, or disassembled to fit changing fashions or even financial needs. This adaptability is evident in Wendela’s waardeboek, where she provides detailed descriptions of individual components and their costs, displaying the fact that these components would hold their worth combined and separated. For example, in 1659, Wendela records that she had 37 diamonds, which she had inherited from her mother, set into two new pendants and added two pearls to each. She notes the additional materials needed, the ‘essenties’, and specifies the expense for the gold and the crafting process, referred to as ‘vatsoen’. This term, which in modern Dutch translates to ‘decency,’ seems to have been historically used in the context of gold- and silversmithing to describe the fashioning or assembly of a piece. Such entries illuminate the ephemeral nature of jewellery in this period, where stones and settings could be rearranged or sold individually if necessary.

The term ‘versetsteenen’ appears to have no known references in existing literature on jewellery history, nor is it flagged in any scholarly work related to Wendela’s collection. Additionally, no other inventories from the period seem to mention this type of diamond, prompting further examination of its possible meaning. The specific cut styles of diamonds are often carefully recorded in inventories, as demonstrated by Wendela’s notation of ‘taefeldiemant’ (table cut diamond). Terms such as table cut, ‘roos’ (rose), and ‘punt’ (point) diamonds were commonly used. This makes it unlikely that Wendela possessed multiple diamonds with entirely unique cuts, particularly given their casual mention within her descriptions. Initially, ‘versetsteenen’ appeared to suggest stones that were set within jewellery, but this interpretation remained inconclusive. A closer phonetic consideration suggests that ‘verset’, when quickly or imprecisely pronounced, may have been intended to signify ‘facet’. When pronounced with an Amsterdam accent, this seems to be even clearer. If this is the case, ‘versetsteenen’ would more logically refer to faceted stones, a term that would encompass any type of polished diamond. A facet is a flat polished section of a diamond, meaning that a facet stone would refer to any diamond with cut and polished surfaces. Given the prevalence of faceted diamonds, and other stones like emeralds or rubies, in seventeenth century jewellery, this interpretation aligns with contemporary terminology and practices.

Portrait and inventory

While Wendela’s written descriptions provide insight into her jewellery collection, they remain brief and do not fully convey the appearance of the pieces. This essay will now turn to her portrait by Adriaen Hanneman as a visual counterpart to the waardeboek. By comparing the jewellery depicted in the painting with her recorded inventory, this section explores how portraiture can supplement and sometimes challenge written records.

The painting was likely commissioned as a wedding portrait, together with a matching portrait of Johan, it presents Wendela in a black gown with white puffed sleeves, a wide and intricately worked flat lace collar, and a dark brown fur shawl. Her short, light brown hair is styled in ringlets and pinned back. The subdued brown background accentuates the six pieces of jewellery she wears, all set with diamonds or pearls. Her attire and accessories assert her status as First Lady of the Republic, signalling wealth and authority without excess.

Although the accuracy of jewellery depictions in portraiture remains uncertain, Hanneman’s painting provides a valuable visual counterpart to Wendela’s jewellery inventory.[3] Several pieces in the portrait correspond with entries in her waardeboek, while others appear to be absent from her descriptions, suggesting possible omissions from the inventory. Hanneman’s attention to detail lends credibility to the depiction of Wendela’s jewellery. The rendering of Wendela’s pearl necklace further supports the idea that he painted from life rather than imagination. Since pearl cultivation was only introduced in the nineteenth century, all pearls in the seventeenth century were natural, making them rare and expensive.[4] Their nacre, or outer layer, could vary significantly in colour and lustre, and their shapes were often irregular. Unlike modern standardized pearls, Wendela’s collection would have likely exhibited a greater variety in appearance. Hanneman captures these minute variations, depicting subtle differences in colour and sheen between individual pearls, reinforcing the likelihood that the jewellery in the portrait reflects pieces she truly owned.

Earrings

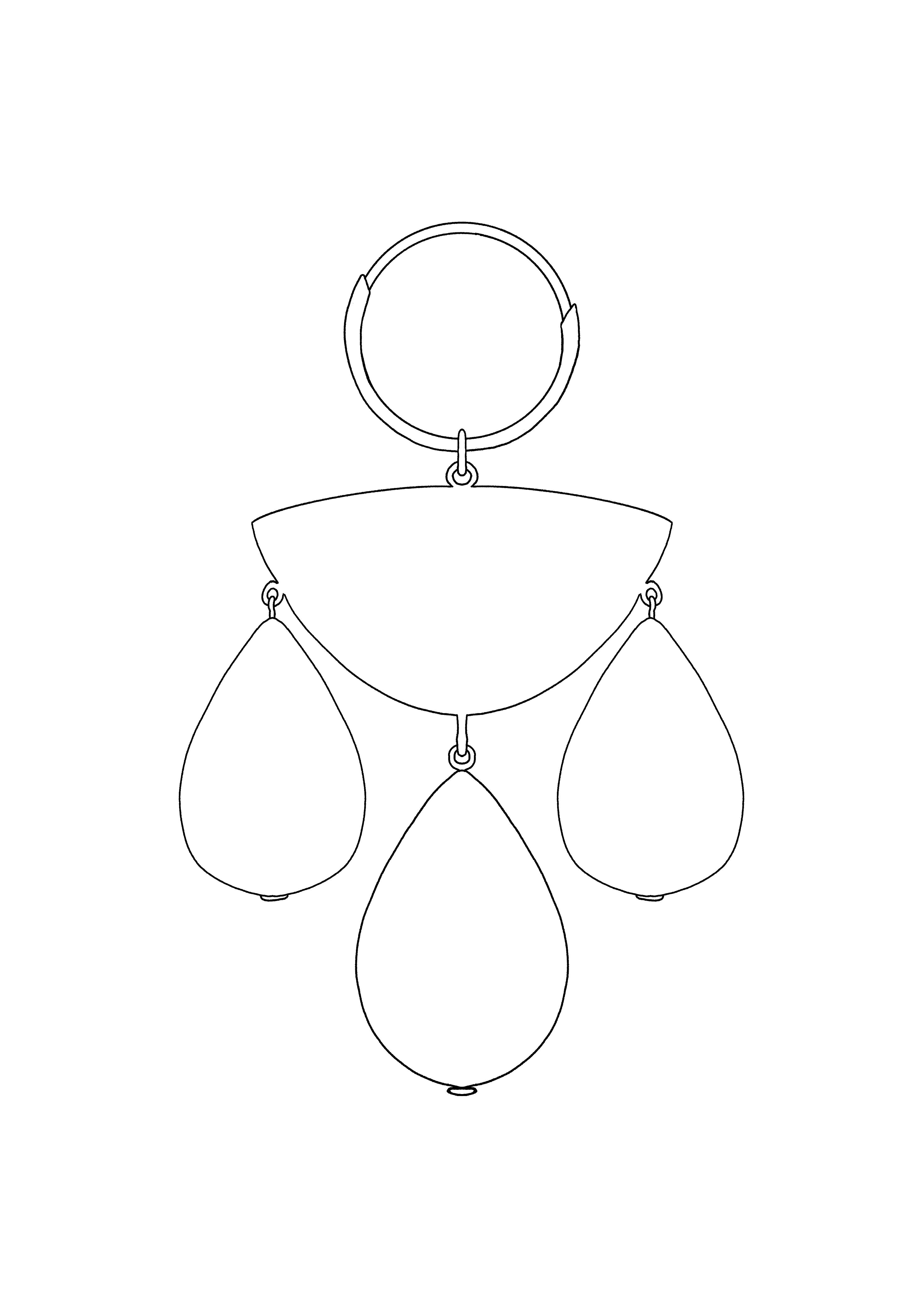

In the portrait, Wendela appears to wear earrings that correlate with the description of the half-moon earrings listed in her waardeboek.[5] The portrait only shows a part of her earrings, two pairs of drop shaped pearls hung on two levels emerge from her curls, while the rest of the earrings remain hidden. These likely match to the earrings described as: ‘Two golden half-moons for the ears, on each 3 pearls, on each 2 pearls with components, together 12 guilders.’ The description and Hanneman’s unclear depiction of the earrings have been put together to create a new drawn rendition to help clarify what these earrings might have looked like. The interpretation has been influenced by the sketches done by Arnold Lulls, a Dutch jeweller who kept a sketchbook from 1585 to 1640.[6] One sketchbook page shows golden earrings, which could resemble the ones worn and described by Wendela.

Since Wendela describes the jewellery so succinctly, two versions of the drawn interpretation have been provided. One shows a potential enamelled side, and the other follows the minimal description from the waardeboek. Wendela was meticulous and correct in the valuations of her items in the waardeboek, however, she does not describe the decorative details of her jewellery. Wendela’s inventory descriptions focus on the quantity and value of the jewellery pieces, not their decorative impact. Other inventories did describe decoration on many types of jewellery, such as enamelled decoration, ‘geamaljeerde’.[7] Many jewels from this period featured intricate embellishments such as floral openwork, blackwork, or enamel on the reverse, decorative elements that remained entirely concealed when viewed from the front.[8] It therefore seems unlikely that Wendela would not have owned any jewellery with decorations. Thus, there is a good chance that Wendela’s earrings could have been enamelled or decorated on one side, as it fit the style of the period. This is also the case for her poinçon and brooch, as these tended to also be decorated with enamel or openwork on the reverse.

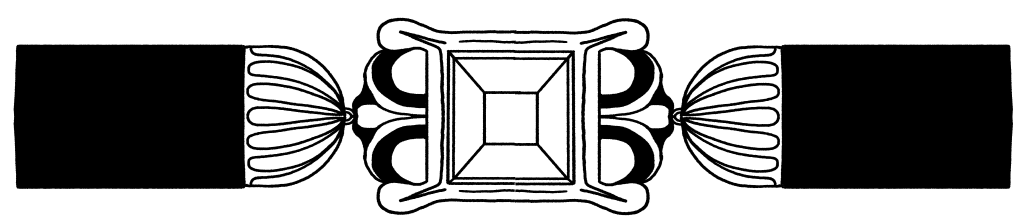

Brooch

The portrait also depicts Wendela wearing a bow-shaped brooch, a ‘strik’, on the middle of her bodice, likely adorned with diamonds. A drawn version has been created to clarify the depicted brooch. This style of brooch was very fashionable in the 1630s, a time where the demand for diamond jewellery boomed.[9] As can be seen in this type of jewellery piece, during the rising popularity of diamond, instead of using detailed narrative metal work or enamelling, jewellery was designed to let the diamonds take centre stage.[10] This particular style of brooch appears to have been especially popular in portraiture, as it recurs frequently across various depictions from the period.[11] However, no ‘strik’ brooches or bow ‘naald’ are explicitly mentioned in her inventory. The only related items are poinçons, which typically refer to hair needles but could occasionally be used as pins and therefore worn as brooches.[12] While it is possible that Wendela referred to brooches as poinçons, her generally meticulous descriptions in the waardeboek make this interpretation uncertain. Conversely, the diamond hairpin she wears in the portrait aligns more directly with the poinçons listed in her inventory, as they seem to be set with diamonds, as she describes her poinçons to be.

(Wedding) ring

The diamond ring visible in the portrait likely corresponds to the table-cut diamond ring Wendela received from Johan de Witt, as described in 1656.[13] During this period, such rings were commonly exchanged at the time of marriage as symbols of unity. Wendela wears the ring on her left hand, which was not traditionally used for wedding rings.[14] However, she may have worn another ring on her right hand, as her waardeboek records multiple rings. One such piece, also a gift from Johan, is described as ‘1 gold double hoop presented by my husband, worth 10 guilders.'[15]

Jacob Cats (1577-1660), the contemporary Dutch moral writer and poet, discusses the role of the wedding ring in his book Houwelick.[16] He emphasizes its significance as a bond between married souls:

'By ons, wanneer de trou op heden is beschreven,

Soo worter aen de bruyt een fijn juweel ghegeven,

Een eygen trou-geschenck van gout off dyamant,

Geen lijff-cieraet alleen, maer oock een ziele-pant.'[17]

'With us, when the marriage has been written,

the bride is given a fine jewel,

a golden or diamond marriage gift of her own,

Not merely an ornament, but a token of the soul.'[18]

This passage underscores the dual role of the wedding ring, not only as an ornament but as a deeply personal token of commitment and unity. Wendela’s diamond ring, likely a gift marking her marriage to Johan, serves as a visual affirmation of this bond, reinforcing the broader cultural and symbolic meanings associated with such jewellery in seventeenth-century Dutch society.

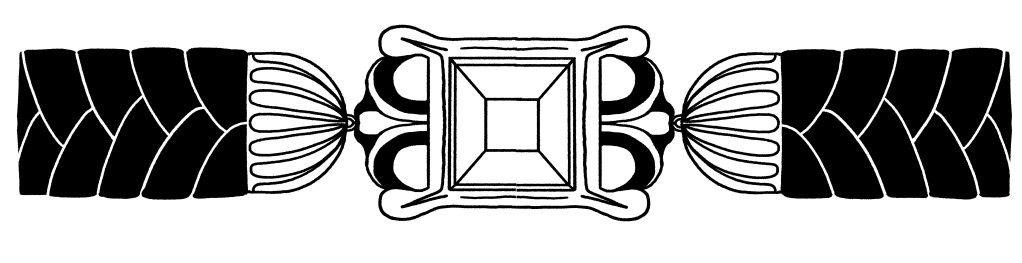

Bracelet

One of the more puzzling aspects of Wendela’s portrait is the bracelet she wears. Unlike her other jewellery, there is no clear mention of a black bracelet or similar item in her waardeboek. The only bracelets she explicitly recorded were braseletten made of pearls, which were especially popular at the time.[19] Efforts to find comparable, black-banded bracelets in other portraits have been inconclusive, leaving both the material and design of Wendela’s uncertain. Several possibilities could explain its appearance, though none are particularly common. The gold and diamond section of the bracelet resembles more familiar designs in which diamonds were set in claw settings for rings. However, it is unusual for this type of setting to be used in bracelets of this kind.

One possibility is that the dark band of the bracelet was made of rolled fabric, a style that does not seem to appear in seventeenth-century portraiture. Another explanation is that it was crafted from braided horsehair, as hair jewellery seems to begin to emerge around this time. However, since materials such as fabric and horsehair are fragile, it is possible that no examples have survived from the seventeenth century. Even so, it remains curious that no similar bracelets have been identified in portraits so far. A further possibility is that the bracelet was composed of small garnets, as garnet bracelets were frequently worn in traditional Dutch attire. However, the absence of any reflective qualities in the painting complicates this interpretation. Given the careful rendering of the diamonds elsewhere in the portrait, it is likely that a beaded bracelet would have been painted with at least some indication of sparkle.

The exact nature of the bracelet remains open to interpretation. Its absence from Wendela’s inventory suggests that she may have only recorded pieces she considered valuable enough to list. This raises the broader question of whether other items, particularly those of lesser monetary or symbolic significance, were also omitted from her records.

Conclusion

Wendela Bicker’s waardeboek provides a unique insight into jewellery culture of the elite in the Dutch Republic. Its omissions, particularly in comparison to her portrait, suggest that not all jewellery was considered significant enough to document, or that certain terms were used flexibly. The gaps in her inventory highlight the challenges of reconstructing historical jewellery collections solely through written sources. By integrating archival descriptions with painted representations, this study demonstrates how portraiture can supplement and, at times, challenge written inventories. Wendela’s jewellery was not static. She valued its components both as assembled pieces and as assets that could be altered over time. The drawn reconstructions of her jewellery provide a way to visualize how these pieces may have looked, offering a more tangible understanding of her collection.

Ultimately, this essay underscores the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in studying seventeenth-century jewellery. Combining textual records, visual sources, and material analysis allows for a richer interpretation of jewellery history.

Endnotes

[1] See appendices, Stadsarchief Amsterdam: 76, 610, folio 47.

[2] Vesna Smit, “Verklarende Woordenlijst Bij Het Memorieboek van Maria van Nesse,” 2022, https://www.regionaalarchiefalkmaar.nl/images/Documenten/Artikelen/Verklarende_woordenlijst_bij_het_memorieboek.pdf.

[3] Monique Rakhorst, “Gedragen En Vastgelegd: Sieraden Uit de Periode 1600-1650” (2023), 90-92.

[4] Gemological Institute of America, “Pearl History and Lore,” Gem Encyclopedia (blog), n.d., https://www.gia.edu/pearl-history-lore.

[5] See appendices, Stadsarchief Amsterdam: 76, 610, folio 47.

[6] Rakhorst, “Gedragen En Vastgelegd”, 16.

[7] Suzanne Van Leeuwen, “‘Met Diamanten Omset’: Hoop Rings in the Northern Netherlands (1600-1700),” The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 71, no. 1 (March 13, 2023): 42–61, https://doi.org/10.52476/trb.13838., 49; M. H. Gans, Juwelen En Mensen (Amsterdam: J.H. de Bussy, 1961), 387, 402.

[8] Provinciaal Diamantmuseum, Een Eeuw van Schittering, Diamantjuwelen Uit de 17de Eeuw (Diamantmuseum, Antwerpen, 1993), 17, 19.

[9] Diamantmuseum, Eeuw van Schittering, 15-19, 23; Monique Rakhorst, “Gedragen En Vastgelegd: Sieraden Uit de Periode 1600-1650” (2023), 14.

[10] Diamantmuseum, Eeuw van Schittering, 15-16.

[11] For instance, see: Portret van drie regentessen van het leprozenhuis in Amsterdam by

Ferdinand Bol (1616–1680), c. 1668, Rijksmuseum or Portret van een jonge vrouw, mogelijk Susanna Reael by Isaack Luttichuys (1616-1673), 1656, Rijksmuseum.

[12] Ineke Huysman and Roosje Peeters, Vrouwen Rondom Johan de Witt (Uitgeverij Catullus, 2024), 213-214.

[13] See appendices, Stadsarchief Amsterdam: 76, 610, folio 47.

[14] Van Leeuwen, “‘Met Diamanten Omset’”, 52.

[15] See appendices, Stadsarchief Amsterdam: 76, 610, folio 47.

[16] Jacob Cats, Houwelick, 1625.

[17] Cats, Houwelick, 1625, 9R.

[18] Translation by author of Cats, Houwelick, 1625, 9R.

[19] Rakhorst, “Gedragen En Vastgelegd”, 18-19.

Leave a comment