Originally in Wendela Magazine

In the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, jewellery was a financial asset, a marker of status, and a way to secure wealth across generations. Especially to women, the portable and valuable items offered women a form of financial security that could be sold, inherited, or gifted, often outside the formal structures of property ownership. Unfortunately, the ways in which seventeenth century women managed, valued, and recorded their collections remain less explored.

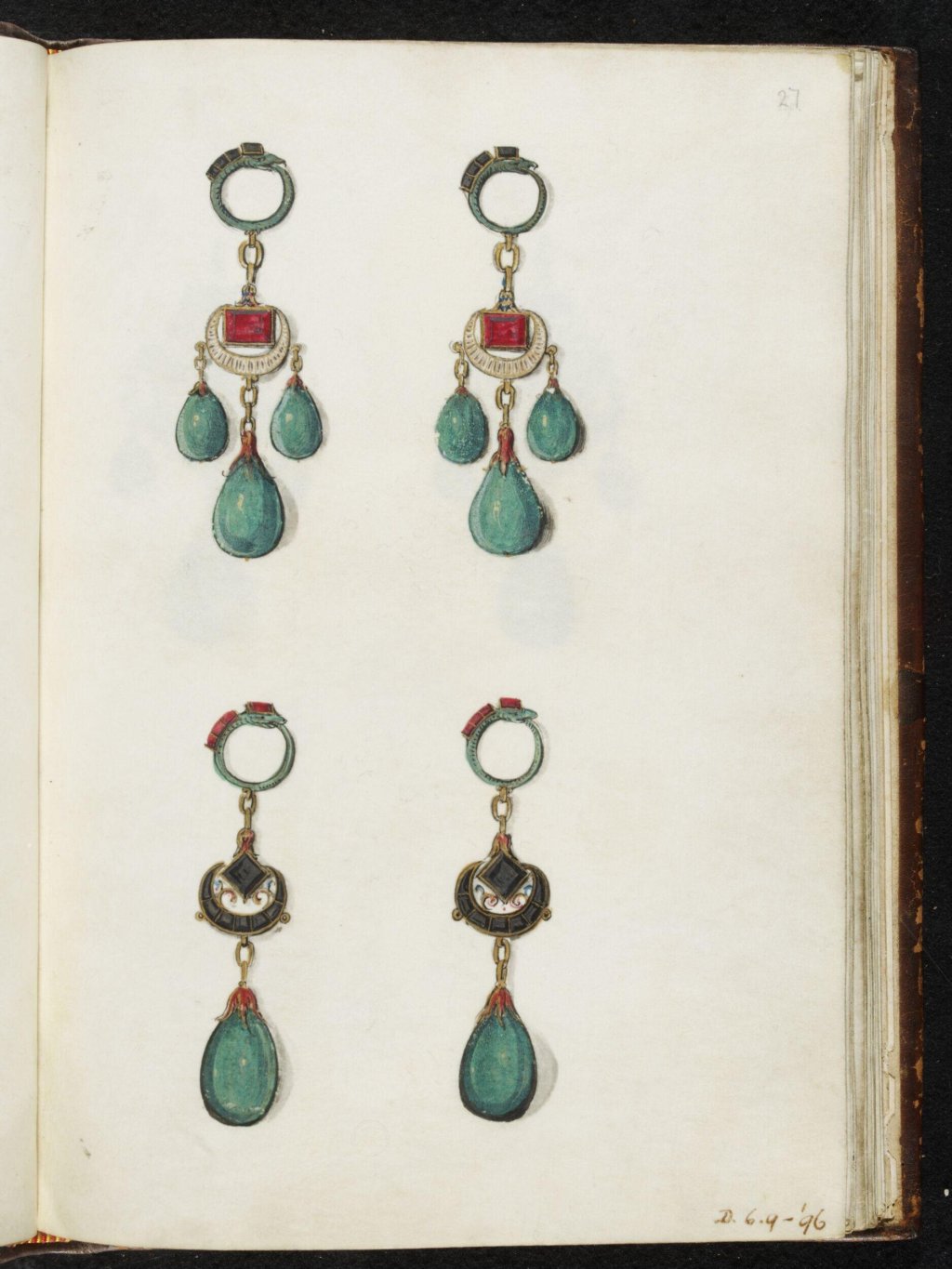

Wendela Bicker’s waardeboek provides a glimpse into how a woman of her standing handled her jewellery collection. While her portrait, 1557, by Adriaen Hanneman, offers a visual representation of some of her pieces, her detailed inventory shows their considerable monetary worth and the methods used to assess their value. This essay examines how Wendela and those around her engaged with jewellery as both a personal and financial asset, examining the ways in which jewellery was appraised and redistributed. In doing so, it highlights how women’s role in managing valuable possessions, even within a financial system largely dominated by men.

Appraisals

Having established what jewellery Wendela owned and how it appears in her portrait and records, this essay will now explore how she and others assessed its value. By examining her own estimations, appraisals, and the role of women in jewellery management, this section highlights the financial and personal significance of her collection, as well as its later sale and redistribution.

Wendela structured her waardeboek with a contents page, dated 1667, in which she alphabetically organized the various sections of the inventory. One of the most significant sections, titled ‘Juweelen en keetenen, penningh’ (jewels and chains, medallions), is valued at 7,500 guilders, exceeding any other category in her records by more than 5,000 guilders. To provide context for this figure, an average worker in the Dutch Republic earned approximately 300 guilders per year.[1] This means that Wendela’s jewellery collection alone was worth the equivalent of 25 years’ wages for an ordinary labourer.

A comparison with earlier records shows that by 1655, Wendela’s jewellery had already been valued at 7,064 guilders. Over the following decade, through acquisitions and transfers, the total sum increased to more than 7,500 guilders by 1664. Despite the immense value of this collection, the process by which these valuations were made is only briefly noted in her waardeboek. At the end of the first section of the jewellery inventory, Wendela states: ‘We have estimated the value of these jewels at 6,000.’ The explicit use of ‘we’ suggests that this estimation was made jointly with her husband, Johan de Witt, indicating that the couple relied on their own knowledge to assess the worth of their jewellery. Most other valuations in the book appear to have been carried out by Wendela herself, demonstrating her familiarity not only with jewellery but also with the valuation of household goods more broadly.

Wendela also seems to have made use of external appraisers, as she had all her jewels appraised on 22 August 1664.[2] This appraisal adjusted the total valuation downward by 333 guilders, a revision she accepted and incorporated into her inventory. The identity of the appraiser remains unknown. It is unclear whether they were a jeweller, a notary, or another trusted individual. The reason behind Wendela’s decision to seek an appraisal is also uncertain, though it was not uncommon to have an inventory or parts of an estate appraised, particularly in preparation for legal or financial transactions. In the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, it was customary for a notary to draw up an estate inventory after a person’s death to facilitate the division of assets among heirs.[3] One possible explanation for Wendela’s decision to have her jewellery appraised in 1664 is the birth of her sixth child, Elisabeth, on 6 June of that year.[4] Although Elisabeth passed away the following year, the appraisal may have been undertaken to prepare for the future division of her collection among her children. This concern for equitable distribution is reflected elsewhere in her inventory, where she recorded which pieces of jewellery had been gifted to her eldest daughter, Anna, by various family members. For example, in 1656, she documented the following entry on spread 48: ‘Presented by my brother van Swieten: 1 poinçon (brooch/hair needle) for my daughter Anna de Witt, containing 9 facet stones, estimated at 90–.’[5]

After Wendela’s early death in 1668, her sister-in-law, Jacoba Bicker, oversaw the appraisal and sale of parts of her jewellery collection to ensure its fair distribution among Wendela’s children.[6] In her correspondence with Johan de Witt, Jacoba details her efforts to secure favourable prices, ultimately achieving a final sale value of 2,650 guilders. This sum exceeded the initial appraisals conducted by Juffrouw van Breen, whose role and qualifications remain unclear.[7] It is unknown whether Van Breen was a professional appraiser or if she had another form of expertise in jewellery valuation. Nevertheless, the fact that this external valuation of jewellery was performed by a woman, is important to underline.

The involvement of Wendela, Jacoba, and Van Breen in these financial transactions highlights the active role women played in managing valuable possessions such as jewellery.[8] Despite male dominance in other financial affairs, Jacoba managed the jewellery negotiations independently, reporting the outcome to Johan rather than requesting his direction. Unlike land or business holdings, jewellery was a form of wealth that women could more readily control and transfer, either through personal decisions or as part of family agreements. Wendela’s detailed inventory already demonstrates her agency in managing her collection, and Jacoba’s handling of the sale further reinforces the extent to which women could exercise financial responsibility in this domain.

Conclusion

Wendela Bicker’s waardeboek offers more than just a list of jewellery and other items. Rather, it reveals how she and other women actively engaged in jewellery valuation, management, and eventual redistribution. From her own assessments to external appraisals and posthumous sales handled by her sister-in-law, the process of valuing and selling her collection was largely overseen by women. While male notaries and merchants often controlled larger financial transactions, jewellery appears to have remained a flexible form of wealth that women could manage with relative independence.

The involvement of Wendela, Jacoba Bicker, and Juffrouw van Breen in these transactions suggests that women played a larger role in financial decision-making than is often assumed. Jewellery was not only a reflection of status but also a practical asset that could be leveraged when needed, providing insight into the ways women navigated wealth and inheritance in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic.

Endnotes

[1] Kees Zandvliet, De 250 Rijksten van de Gouden Eeuw ( Rijksmuseum Publishing, 2006), XIII.

[2] See appendices, spread 49.

[3] Th.F Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, Boedelinventarissen (Den Haag: Instituut voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis, 1995), https://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/pdf/Broncommentaren/voorlopig/Broncommentaren_2-001_073.pdf, 6.

[4] Els Kloek, “Bicker, Wendela (1635-1668),” Knaw.nl, 2014, https://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/vrouwenlexicon/lemmata/data/Bicker; see timeline.

[5] See appendices, spread 47; Ineke Huysman and Roosje Peeters, Vrouwen Rondom Johan de Witt (Uitgeverij Catullus, 2024), 213-214.

[6] Saskia Kuus, “De Verkoop van Een Aantal van Wendela’s Juwelen Door Jacoba Bicker – Johan de Witt,” Johandewitt.nl (blog), October 24, 2020, https://johandewitt.nl/de-verkoop-van-een-aantal-van-wendelas-juwelen-door-jacoba-bicker/#_edn5.

[7] Huysman, Vrouwen, 216-217.

[8] Huysman, Vrouwen, 217.

Leave a comment