My undergraduate dissertation for completion of the degree of the History of Art (Honours, Edinburgh University)

In seventeenth-century Dutch visual culture, death was not concealed or removed from daily life. This dissertation examines child portraiture and child death portraiture in the Dutch Republic as a response to a society shaped by high child mortality, religious reform, and a persistent awareness of life’s fragility. Rather than approaching these works as morbid exceptions, the study treats them as meaningful objects embedded in domestic interiors, material culture, and systems of belief.

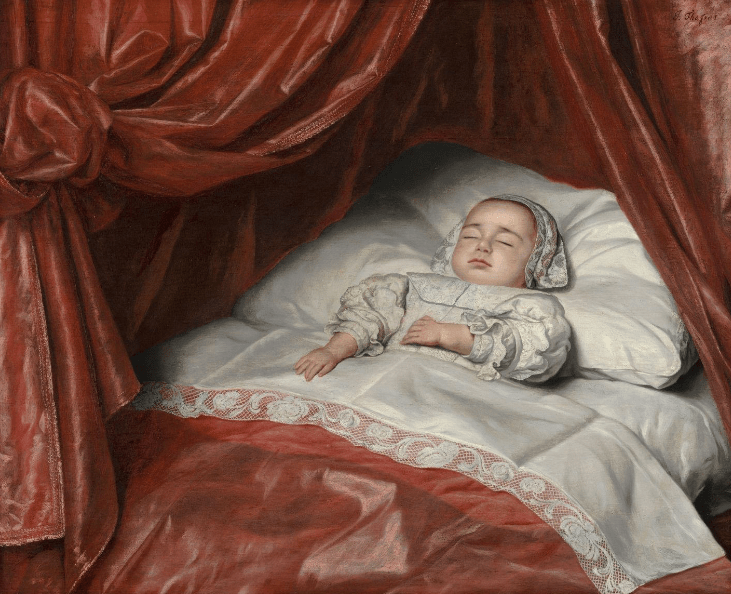

Child death portraits were not marginal images. In a society where nearly half of all children did not survive to adulthood, death was a shared and anticipated reality. Portraiture offered parents a way to engage with this reality visually and materially. These paintings did not simply record likeness. They functioned as sites of protection, memory, and emotional continuity, allowing the child to remain present within the household after death.

A central concern of the dissertation is the role of material culture in shaping the meaning and function of these images. Objects frequently depicted in children’s portraits such as silver rattles, coral beads, pearls, swaddling cloths, and fall hats were not incidental. They were objects drawn from daily life, closely associated with the child’s body, and often invested with protective or moral significance. When represented in paint, these items linked the two-dimensional image to lived, sensory experience. The viewer did not only see the child but remembered the weight of a rattle, the sound of its bells, or the feel of pearls against skin.

Protection emerges as a key theme throughout the study, operating on multiple levels. On a practical level, early modern childcare was deeply entangled with concerns about health, medicine, and bodily vulnerability. Swaddling, regulated play, and protective headgear reflected a culture anxious about illness and physical harm. At the same time, materials such as coral, animal teeth, and pearls were believed to possess protective properties that extended beyond the physical body. These objects guarded against illness, moral corruption, and unseen threats, embedding care and fear into the child’s immediate material environment.

Religious change also played a decisive role. Calvinism reshaped attitudes toward death and mourning by removing funerary ritual from the church and limiting visual expressions of grief within religious space. As a result, the home became a primary site for negotiating loss. Child death portraits can be understood as filling this ritual emptiness. They offered a visual language through which parents could grieve, remember, and preserve familial bonds without relying on ecclesiastical imagery.

Significantly, the dissertation shows that death portraits often diverge from the visual strategies used in portraits of living children. Familiar protective objects are frequently absent. Instead, new forms of representation appear: children depicted as angels, idealised pastoral figures, or serene bodies removed from earthly time. These images do not deny death but reframe it. The emphasis shifts from protection of the body to transcendence of mortality, allowing the child to exist beyond the threats that once necessitated material safeguards.

Throughout, the study argues for a closer integration of art history and material culture. By moving beyond the picture plane and considering how objects operated in both painted and physical form, the dissertation highlights the importance of the sensorium in early modern visual culture. Memory, touch, sound, and bodily association were integral to how these portraits functioned and how they were experienced within the home.

Ultimately, this research seeks to reframe child (death) portraiture in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic not as a niche or anomalous genre, but as a deeply embedded cultural practice. These images reveal how parents navigated fear, care, belief, and loss through objects and images that made death visible, bearable, and meaningful.

You can download and read my dissertation on the Thesis library of Museum Tot Zover, Amsterdam.

Leave a comment